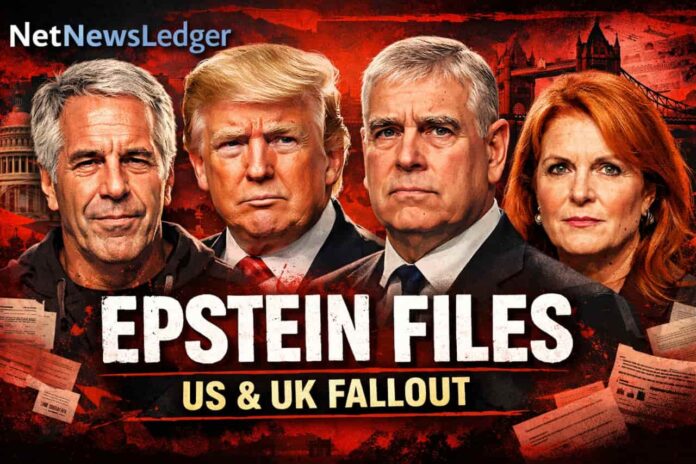

A scandal that became a stress test for institutions

The renewed obsession with the “Epstein Files” in the U.S. and Britain isn’t just voyeurism or celebrity gossip—it’s a public referendum on whether the powerful are held to the same standards as everyone else.

In the United States, a flood of documents tied to Jeffrey Epstein’s investigations has been released under the Epstein Files Transparency Act, with the Justice Department saying it has now published roughly 3.5 million pages, including thousands of videos and images. That scale—and the politics surrounding what’s still redacted—has driven the story into nightly headlines and late-night comedy alike.

In Britain, the same disclosures have re-energized scrutiny of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor (widely known for years as Prince Andrew) and renewed questions about how proximity to Epstein was handled by elites, institutions, and gatekeepers.

What are the “Epstein Files,” really?

The phrase “Epstein Files” is a catch-all for investigative and prosecutorial material: emails, contact lists, interview notes, travel references, and evidence seized during inquiries into Epstein and his associate Ghislaine Maxwell—alongside court records and related documents. The latest releases are controversial for two reasons at the same time:

-

They contain names of famous and influential people (sometimes repeatedly), and

-

A name appearing in files is not proof of wrongdoing—it can reflect anything from a social contact to an administrative reference.

That tension fuels the public demand: people want transparency about who enabled Epstein and who escaped accountability—without destroying innocent reputations through guilt-by-association.

Why the files are so important: three big reasons

1) They keep the focus on victims—and on how the system failed them

One of the most consequential “why it matters” points is that the Epstein case is widely viewed as a long-running failure of the justice system: lenient outcomes, missed chances, and a sense that Epstein’s wealth bought time and protection. Major international coverage has framed the saga as decades of institutional negligence that came at the expense of victims.

That’s not abstract. Survivors and their advocates argue transparency is essential to identifying enablers, correcting failures, and preventing repeat patterns where exploitation is minimized until it becomes politically unavoidable.

2) They expose how power networks operate

Epstein’s influence wasn’t just criminal—it was social and transactional, involving introductions, philanthropy, prestige, and access. The files matter because they show how “respectability” can be manufactured around predators through wealthy circles, institutions, and the people who choose silence over consequences.

That’s why the story keeps landing: it isn’t only about Epstein, it’s about the ecosystem that made Epstein possible.

3) They test whether transparency can coexist with responsible redaction

The rollout has been dogged by redaction controversies—who gets protected, and why. The Wall Street Journal reported that victim identities were exposed in released materials, intensifying outrage that survivors could be harmed again while powerful names remain hidden.

That failure matters in a practical way: if government can’t protect victims while disclosing records, transparency becomes another kind of harm.

The Trump question—and the danger of “name math”

You referenced a claim that President Donald Trump is mentioned “one million times” in unredacted files and that he’s said there is “nothing there.” What can responsibly be said is this:

-

Trump has publicly argued that photos and associations can unfairly ruin reputations, framing some appearances as people who “really had nothing to do with” Epstein.

-

In the political fight over the releases, late-night coverage and some lawmakers have repeated an allegation that Trump’s name appears “over a million times,” attributed to Rep. Jamie Raskin—an assertion that has not been independently verified publicly and may be rhetorical shorthand for “frequent references” across a massive document dump.

The key journalistic point for readers: frequency of mentions is not a finding of guilt. In datasets this large, the same person can be referenced repeatedly through email chains, contact lists, scheduling, news clippings, or legal filings. The files can raise questions—and do—but they don’t automatically answer them.

Britain’s royal fallout: Andrew and Sarah Ferguson in the spotlight

Across the Atlantic, the Epstein disclosures remain combustible because of the monarchy’s symbolic role: the Crown’s legitimacy depends heavily on public trust.

-

UK reporting has described intensifying pressure on Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor amid claims and investigations tied to his Epstein links, with senior prosecution leadership emphasizing “nobody is above the law.”

-

The public and political reaction isn’t only about allegations of personal conduct; it also concerns judgment, access, and whether official roles were used inappropriately.

-

Sarah Ferguson’s connection has also drawn renewed attention, including reporting on communications that framed Epstein warmly—fueling reputational damage and institutional distancing.

For Britain, the Epstein Files function as a credibility test: what did the Palace know, what did it ignore, and how does a modern monarchy handle scandal in the age of searchable archives?

The Thunder Bay angle: why this matters here, too

It’s tempting for Canadians to treat Epstein as a U.S.-UK celebrity spectacle. But the underlying issue—human trafficking and exploitation networks—is not foreign to Northwestern Ontario.

Statistics Canada reporting shows that between 2014 and 2024, Thunder Bay had one of the highest average annual police-reported rates of human trafficking among Canadian CMAs—and in 2024 specifically, Thunder Bay remained among the highest.

That doesn’t mean Epstein-style elite trafficking is a local pattern. It means the broader reality—recruitment, coercion, exploitation, and community harm—is present here. So the “Epstein Files” obsession can be used productively if it drives attention toward:

-

survivor-centred services,

-

prevention and public education,

-

enforcement resources, and

-

a community understanding that trafficking is often hidden in plain sight.

Ontario has framed anti-trafficking investments as province-wide priorities, including supports aimed at victims and survivors.

Why late-night keeps returning to it

Late-night monologues work when an audience already feels a shared frustration. The Epstein Files story is tailor-made: a notorious crime, elite connections, secrecy, redactions, and institutions that look defensive. That mix produces jokes—but the jokes are doing something else, too: they’re reflecting and reinforcing a public demand for consequences that match the crime.

Bottom line

The Epstein Files are important because they sit at the intersection of sexual exploitation, elite impunity, and institutional credibility. They force governments and powerful institutions to answer uncomfortable questions: Who was protected? Who was ignored? What’s being withheld? And can transparency happen without hurting victims all over again?

For readers, the most meaningful takeaway isn’t celebrity scandal—it’s the reminder that trafficking thrives where power goes unchecked and communities look away.