THUNDER BAY – Across Turtle Island (North America), winter arrives in many languages and many landscapes—coastal rains, prairie winds, deep-forest snow, northern darkness lit by stars and fire.

Indigenous Nations have always adapted to these seasonal rhythms in distinct ways, shaped by homelands, food systems, and teachings carried through families. There is no single “Indigenous winter tradition,” but there are shared themes that return again and again: gratitude, renewal, community care, and the steady work of keeping stories alive.

Today, winter for many Indigenous people also includes Christmas—sometimes embraced, sometimes held at arm’s length, and often woven together with older responsibilities and community practices. What follows is a gentle overview of a few winter-season traditions, offered with respect and with an important reminder: some ceremonies are private, and what is shared publicly is only a small portion of what winter means within each Nation.

Winter as a time of renewal and responsibility

In many Indigenous worldviews, winter is not “empty time.” It is a season for resetting relationships—within the community, with the natural world, and with the spirit of gratitude itself.

Among the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, a well-known winter observance is the Midwinter Ceremony, a period that is often described publicly as a time of renewal for the new year and for community responsibilities. Some Haudenosaunee sources describe it as occurring around January and lasting about a week, linked to the new moon and community practices that renew the mind and responsibilities for the coming year.

What matters most here isn’t the schedule—it’s the intention: winter is a time to turn toward one another, to remember teachings, and to begin again.

Winter solstice traditions in the Southwest

In the Southwest, the winter solstice can be a powerful marker of time—when days are shortest and the return of longer light is welcomed.

The Hopi are widely associated in public sources with Soyal (Soyalangwul), a winter solstice ceremony tied to renewal and the turning of the season. Public-facing descriptions emphasize prayer, purification, and community preparation for the year ahead.

It’s also important to remember that many ceremonies in Pueblo and Hopi communities are not performances—they are living responsibilities. Some elements may be closed to visitors, and that boundary is part of respect.

Among the Zuni, the Shalako is often described in museum and public references as one of the most important events in the religious calendar, held in December and connected with blessing and thanksgiving. Multiple public sources note that the ceremony has been closed to non-Zuni attendance except by invitation.

The takeaway for readers is simple: even when we learn the names of winter ceremonies, we don’t automatically gain access—and we don’t need access to be respectful.

Northern winter: light, warmth, and the dignity of care

In Inuit homelands, winter has always demanded skill, patience, and collective care. One widely recognized cultural symbol is the qulliq, a traditional oil lamp historically used for heat and light, and still used in ceremonial contexts today. Public sources describe the qulliq as both practical and deeply meaningful—light that gathers people together in the long season.

Even when traditions vary from community to community, winter often highlights the same quiet teaching: warmth is shared. It’s shared through food, through visiting, through checking on Elders, through making sure no one is left alone.

Story season: when teachings come indoors

In many Nations, winter is also known—publicly, in broad terms—as a time when teachings and stories are told, especially when the work of the warmer months slows down. Storytelling isn’t “entertainment” in the usual sense; it can be education, ethics, history, humour, and survival knowledge carried all at once.

You can think of winter stories as a kind of hearth: not just something you listen to, but something you gather around. In many communities today, this continues through family visits, language revitalization circles, community feasts, and winter gatherings where youth and Elders are intentionally brought together.

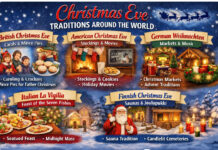

Christmas in Indigenous communities: many ways of holding it

Christmas has a complex history in Indigenous North America. For some families, it brings joy and familiarity: church services, nativity plays, carols in community halls, gift exchanges, and big meals that feel like home. For others, it can also stir grief because of the role Christian institutions played in assimilation and residential/boarding school systems. Many communities hold both truths at once.

Because of that, Christmas may show up in a few different ways:

-

As community care: toy drives, food hampers, and community dinners—often organized through band offices, friendship centres, churches, and grassroots volunteers.

-

As family gathering time: travel home when possible, visiting relatives, and making room at the table for whoever needs it.

-

As a blended season: Christmas alongside older winter responsibilities—ceremonies, language work, seasonal teachings, or simply the continued practice of being in good relation.

In many places, the most meaningful “Christmas tradition” is not a specific ritual—it’s the way the season becomes a reason to return home, share food, and look after each other.

A respectful way to participate (especially as a guest)

If you’re reading this as a visitor—someone learning about Indigenous winter traditions outside your own community—there are gentle, practical ways to show respect:

-

Follow community guidance. If an event is closed, it’s closed. If photography is not allowed, don’t ask for exceptions.

-

Support Indigenous artists and vendors during holiday markets and winter craft fairs, and learn whose territory you’re on.

-

Choose learning that is offered freely. Museum pages, cultural centre resources, public talks, and Nation-run websites are good starting places.

-

Let winter be quieter. Not everything needs to be turned into content. Sometimes the most respectful posture is simply listening.

Closing: winter teaches us how to keep the fire

Winter can be hard. It can also be clarifying. Across Indigenous North America, winter traditions—whether solstice observances, midwinter ceremonies, community feasts, storytelling nights, or Christmas gatherings—often return to the same steady centre: we survive by remembering one another.

In that way, winter is not only a season we endure. It is a season that teaches us how to keep the fire—how to feed it with gratitude, attention, and care until the light returns.