THUNDER BAY – LIVING – The holiday season is a time for gathering, reflection, and connection. It can also be a time when deep conversations surface—sometimes unexpectedly.

For many Indigenous people, holidays can bring difficult discussions about identity, rights, and history. When friends or family raise questions—often without harmful intent—about topics like Residential Schools, Treaty Rights, or taxation, it can lead to tension.

The same topics might come under around the dining room table in your home over the holidays, and often by individuals with little understanding of the issues, or realization that their views are inaccurate.

If that happens in your home this year, and good old “Uncle Dave” starts blustering off again on his rigid set of self set facts, in reality is it an opportunity: a chance to share truth, calmly and clearly.

Here is a simple guide to help navigate these conversations with knowledge and respect.

Residential Schools and Truth & Reconciliation

Canada’s residential school system was in place for over 150 years. More than 150,000 First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children were taken from their families and placed in institutions run by churches and funded by the government.

These schools were designed not to educate, but to assimilate Indigenous children by erasing their languages, cultures, and identities. Many children experienced abuse, and thousands never returned home.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) released its final report, with 94 Calls to Action that outline how Canada can begin to heal from this legacy. These are not just symbolic steps—they include changes to education, justice, child welfare, and health care. They are an invitation for all Canadians to take part in reconciliation, through learning, acknowledging, and acting.

Treaty Rights Are Responsibilities, Not Special Privileges

Treaties are not ancient documents—they are living agreements between First Nations and the Crown, meant to define a relationship of mutual respect and sharing of the land. Treaties include commitments that still hold legal and moral weight today. These include the right to hunt and fish, and in some cases, access to education or health services.

Importantly, Treaty Rights are not handouts. They are promises made in exchange for access to land and resources. They come with responsibilities on both sides—Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike.

Honouring them is not about giving more to one group—it’s about keeping the word that Canada gave, often in writing and sealed by ceremony.

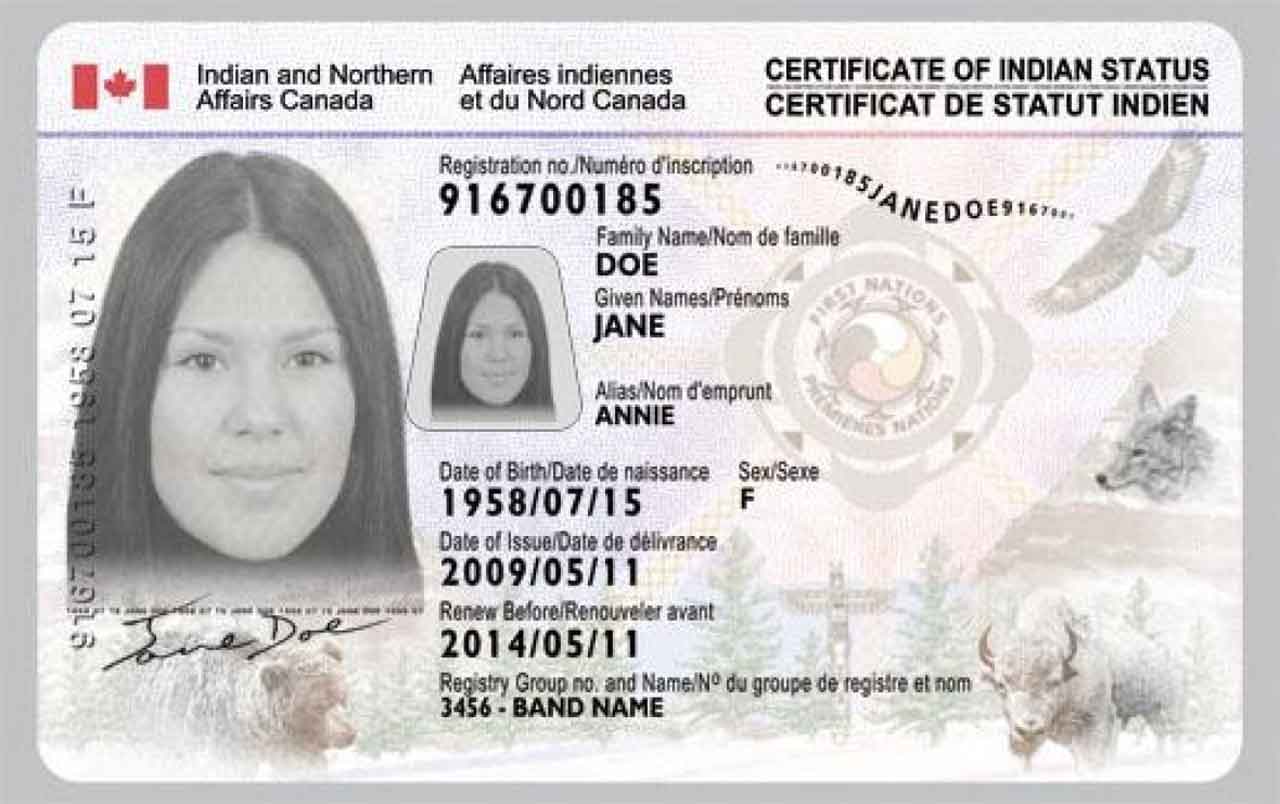

What About Status Cards and Taxes?

One common question is whether Indigenous people “pay taxes.” The answer is: it depends.

Under the Indian Act, some tax exemptions exist for Status First Nations people, but they are specific and limited. For example, if a Status person lives and works on a reserve, their income may be tax-exempt. Purchases made on-reserve may also be tax-exempt. However, most Indigenous people in Canada do pay income taxes, sales taxes, and property taxes—just like everyone else. The exemption is tied to land and legal status, not race.

A Status Card is simply government-issued ID that proves a person is recognized as a Status Indian under the Indian Act. It is not a “perk”—it reflects a legal relationship between First Nations individuals and the federal government, including rights and responsibilities defined by historical treaties and policies.

“Do All Indigenous People Get Free University?”

This is another myth that often surfaces. Some First Nations have agreements or funds to help pay for post-secondary education for their members—but not all. Funding is limited, competitive, and does not cover everyone. Métis and Inuit peoples have separate funding streams, often with their own rules and limits.

In reality, many Indigenous students face financial barriers to education. They are underrepresented at universities, and those who do attend may carry heavy burdens—cultural, emotional, or economic. Rather than receiving “free” education, many work hard to succeed in systems that were not designed with them in mind.

So How Do We Talk About These Topics?

-

Start with listening. If someone is Indigenous and chooses to share their story, listen with care. If you are Indigenous, know that you are not obligated to educate others, especially if the conversation feels unsafe.

-

Use facts, not emotion. Misinformation is often rooted in confusion, not malice. Sharing calmly, with truth and clarity, often has more impact than heated debate.

-

Acknowledge complexity. These are not simple issues. They are layered with history, law, culture, and personal experience. It’s okay to say, “I don’t know, but I can find out.”

-

Encourage learning. There are many accessible resources available—from the TRC report to Indigenous-led podcasts, documentaries, and books. Suggesting a resource can be more productive than an argument.

This holiday season, as we gather around tables and fireplaces, let’s make room for truth. Not to win debates, but to build understanding. Reconciliation is not just a political process—it’s a personal one. Every respectful conversation is a step forward.